Messages for China: linguistic considerations and beyond

My own dealings with this particular aspect inhabit primarily the Chinese language space (save for some fleeting escapades with Spanish in my youth). Aside from cultural understanding, location is something that can really highlight the subtle yet decisive differences in the Chinese language that vary depending on which region you’re targeting. The Chinese language is composed of seven major varieties; and while Mandarin rules the roost, an understanding of nuance and the cultural impact of local variants will certainly get you places. On a macro scale, this is exemplified in some of the differences present in the Simplified and Traditional Chinese versions of Messages in the Deep, which I’ll go into later.

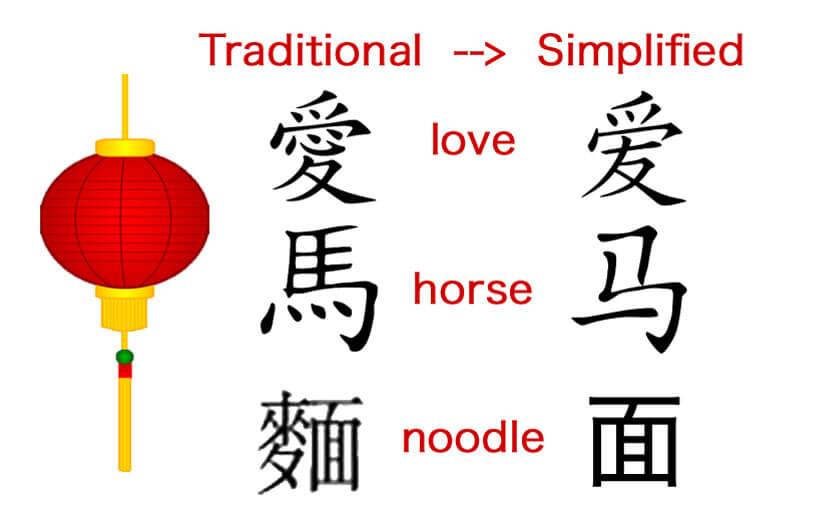

Given the increasing prominence of all things Sino-side in recent years we devised a plan to have the piece translated, coded and uploaded to present to contacts and clients in the region. Given our involvement in Hong Kong and the sheer size and potential prospects in Mainland China, we opted to have the piece translated into both Simplified and Traditional Chinese; two variants of written standard Chinese that, although when read in standardised settings have the same meaning, are probably best explained with this image:

And no, as a vegetarian I can’t say I love horse noodles. (sites.psu.edu)

What does the word “standardised” mean when talking about Chinese?

Before I delve in, here’s just a quick note on what is meant when I use the word “standardised” when talking about Chinese. This really just refers to written Chinese in formal settings which, whether it’s written in Simplified or Traditional characters, will almost always employ the same words and sentence structure while meaning the same thing across both variants, regardless of whether you’re reading it as a Chinese speaker from Beijing, Hong Kong, Singapore or Weston-Super-Mare. As such, this is separate to the differences you encounter when dealing with spoken variations; an entirely different kettle of fish that I’m sure I’ll address in one way or another in a blog post further down the line.

Being “Mainland China friendly”

I’ll skip straight to possibly the largest linguistic challenge of the Messages translation project, which was ensuring the Simplified Chinese version was, in short, “Mainland China –friendly.” Now, I’m sure most of us are familiar with the Chinese internet’s, shall we say, somewhat restrictive approach to the use of certain words, phrases and concepts among other headaches. As a former China-based writer and editor I’m relatively familiar with this particular dilemma and, as expected, it reared its fickle head during the translation of Messages into Simplified Chinese. Among other things this required a euphemised re-wording of some of the content referring to stopping internet censorship in the last few paragraphs, regardless of how tempting it was to pounce upon the irony.

Here’s an image of a section of the Traditional and Simplified Chinese versions which visualises the differences. Notice the difference in the amount of text in the first one…

Messages – Simplified Chinese

Messages – Traditional Chinese

Ideas through idioms

Going further into the linguistic fray, we tried to make sure in both versions that, where relevant, the colourfully poetic world of Chinese idioms (or “chengyu”/成语) was favoured over standard word for word translation. Something like this is always good to look out for and consider when you’re facing language localisation, looking for a worthy supplier or are reviewing translation work. I myself usually favour the inclusion of such nuances – the types that have no direct English equivalent – to convey the meaning you’re after as opposed to “straight” translation.

For Messages in the Deep, here a couple examples from sentences within the piece that deploy this method:

- Messages English: The severity of the impact highlighted how crucial the Internet has become to the structures of the global economy.

- Messages Chinese: 这次重大事件的重要性强调了互联网在全球经济中举足轻重的地位。

Of course, the sentences convey the same meaning, though extra oomph and credibility is added to the sentence however by the use of this idiom: 举足轻重. The phrase literally means “a foot’s move sways the balance”, which is often interpreted as a compound verb meaning “to hold power”.

- Messages English: Kenya has seen mobile Internet access enable people across the country to transfer money through their mobile phones, proving valuable for the millions of citizens lacking bank accounts.

- Messages Chinese: 在肯尼亚,成千上万没有银行账号的公民感受到移动网络的价值,他们通过互联网用手机进行转账。

Here, the idiom 成千上万 is employed, meaning “by the thousands and tens of thousands”, and is often used as a romantic way to emphasise a particularly large number.

Tailored translation: contextual linguistics

Backtracking to my initial reference to the notion of “Standard Chinese”, I’d just like to look at one more defining aspect of tailored translation before this blog post fully slides into a Chinese lesson (though my rates are reasonable). One way of looking at written Chinese is to differentiate between the use of formal and informal language, with the former often referred to as “officialese (官话).” It may sound slightly Orwellian, though officialese is often the lingo of choice for written Chinese that appears in the context of news programmes, formal documents, reports and also articles like Messages in the Deep; with the free-flowing, colloquial-friendly brand of journalism that nowadays inhabits even the biggest Western media outlets rather lacklustre in counterpart Chinese settings. What this means in terms of translation is that there are sets of completely different characters and terms that are used to convey the same meanings that you’d usually see in more informal settings. Again, this is another parameter that ticks the boxes of good localisation and the same concept should be resonated duly across other languages.

Here are some quick examples we used throughout Messages:

- Formal term “因此”, meaning “as a result/consequently” used instead of informal variant “所以”

- “如此” meaning “in this way” used instead of “这样的”

- “然而” meaning “however/yet” used instead of “但是”

- “正如” meaning “just as” used instead of “就像”

One Final Thing…

Hopefully I’ve provided a little useful insight into some of the things that are worth considering when you go down the route of proper linguistic localisation as part of the international SEO package. If anything, I hope this lovingly concise translated sentence illustrates some of what I’ve been rambling on about:

- Messages English: It remains unclear how it will be protected from US or British tapping.

- Messages Chinese: 然而如何使该电缆远离英美的窃听,尚未明朗。

And here’s a few reasons why:

- Use of aforementioned formal term “然而”

- Use of condensed term “英美” meaning “America and Britain/Anglo-American” as opposed to the less elegant, more drawn-out term “美国和英国”

- “尚未明朗”. Lovely little phrase, with “尚未” (not yet) being a nicer variant of “还不是” and “明朗” (clear/obvious) used instead of “清楚”.

Thanks for tuning in! There’ll be more to come soon on the topic of all things international though for now do feel free to share any thoughts you have in the comment boxes below.

Jim McCormick

This was a really insightful article. Never before have I seen such a detailed description of how idioms are translated between languages. I like that you started the article by saying localization is about understanding the culture of your target market, and then logically proved how that is actually executed.

Thanks for the info

Jim McCormick

Owain Lloyd-Williams

Hi Jim,

Many thanks for your kind words! I’m glad you found the article insightful. I do love getting stuck into linguistic and cultural nuances when it comes to topics such as this – there’s often so much to be said on each language and an awful lot to consider, especially with languages like Chinese.