1. Understand the brief

If you’re writing for a client, ask them to send over a detailed brief before you start work. Find out the purpose of the project and get an idea of how much research is involved, so you can plan (and price!) your time accordingly.

Don’t be afraid to ask a lot of questions; you might feel like you’re being a nuisance, but it’s better than learning you’ve written 5,000 words about what it takes to become a barista rather than a barrister.

Make sure you absorb your client’s brand guidelines and get to know their audience. Brands spend a lot of time building an identity and they’ll expect you to protect it; they might prefer a witty tone of voice – like Groupon – or for some unbeknown reason, they may have imposed a blanket ban on using a particular adjective.

Even if you think you know your client inside out, it’s a good idea to first send over a small sample of copy to check you’re on the right track.

2. Respect the research

Research is the single most important part of writing good copy. “Write what you know” might sound like smart advice, but as a copywriter, you’ll be expected to pass as an authority on a topic you’ve had to spend the past 15 minutes reading about on Wikipedia.

In some cases, you may be provided with some background research, but if you’re taking on this responsibility yourself, you should start with a few online searches around your topic area. Identify a list of relevant – and credible – articles and use Google Scholar to find any interesting studies. Save anything that you want to reference and try to track down the original source.

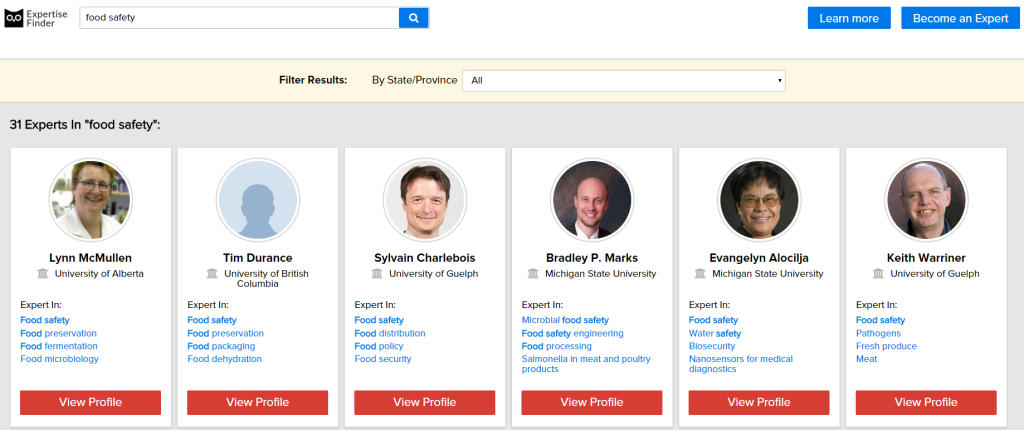

Better still, speak to people who are experts on your subject. See who’s already been quoted in other articles, scour Twitter or use a website like Expertise Finder to see if there are any academics that specialise in your topic.

3. Tell a compelling story

Storytelling is what good writing is all about. Your copy doesn’t necessarily need a clear narrative (e.g. list articles), but it should be driven by a core idea that can be summed up in a single statement and easily understood by a friend who has no prior knowledge of the topic area.

In a typical creative structure, you’ll expand on your friend-proof statement in a short and punchy introduction, before seamlessly moving on to make your main case; you’ll provide some balance, maybe make some predictions, and use your conclusion to revisit the central theme and really tie things together.

You should use headings like visual signposts and it’s often helpful to introduce each section with a brief synopsis that connects the copy back to the central theme.

4. Vomit first, edit later

Tavi Gevinson, the teenage editor of Rookie magazine, told Longform podcast: “I feel like writing is like a little bit of vomiting and mostly editing.”

If you’ve got multiple projects to juggle, your schedule might not afford you the leisure of massaging your copy into shape through multiple revisions, but it’s crucial that you factor editing time into your project plan, as this is where the real work gets done.

Your first draft should tick off all the main points and come in – more or less – around the word count specified. Don’t waste your time agonising over a sentence that seems too long or a metaphor that feels clumsy, as this is only going to drag your unfinished project closer towards the deadline.

Instead, highlight any parts of the text that are giving you trouble, write something else to get your creative juices following again and revisit any nagging details with a fresh pair of eyes later.

5. Optimise for the reader

Thankfully, copywriters no longer have to worry about anything as mind-numbing as keyword density. That’s not to say that SEO best practice is no longer important: you still need to ensure the primary keywords your page is targeting are included in the title, headers and interspersed throughout the body of your copy (be careful not to overdo it).

However, it’s far more important to think about optimising your copy for your readers than simply for search engines. Content marketing is driven by factors such as length, narrative, relevance and uniqueness. If your copy delivers what your title promises, you’ll increase the chances of people sharing and linking to your content immeasurably.

Web pages should contain at least 300 words of unique copy to give people the best chance of finding them through search, but business website Quartz works on the theory that: “Articles of between 500 and 800 words are too long to be shareable and too short to be in-depth.”

Don’t pad out your copy for the sake of it. You need to be a brutal self-editor and – to borrow an old writing cliché – you need to “kill your darlings” to ensure that every word on the page has fought to keep its place.

6. Write an attention-grabbing title

Advertising guru David Ogilvy famously said: “On the average, five times as many people read the headlines as read the body copy.”

Your title is your one shot to get your readers’ attention and convince them that you have something interesting to say. It’s often best to save your title until last, as you’ll have a better understanding of what your copy offers.

In the book ‘Made to Stick,’ by brothers Chip and Dan Heath, it’s explained that good ideas are more predictable than bad ideas, as they tend to follow a pattern. The same is true for title writing; there is good reason that the internet is awash with ‘how to’ and ‘list’ headlines, as they can be annoyingly effective.

Here are some other templates you can use for writing titles:

Questions: What Kind of Dog Are You? What Happens When You Give up Deodorant for a Week?

Opinions disguised as fact: What You Think You Know about the Web is Wrong, Japanese and Siberian Flying Squirrels are the Cutest Animals on Earth

Commands: Take Back your Mornings, Get Gorgeous Now

Curiosity gaps: This is What Happens When You Don’t Get Enough Sleep, This is Your Body without Water, The Secret Dual Lives of People Living With Mental Illness, Books That Predicted the Future

As you’re writing for the web, remember that Google truncates page titles (this doesn’t need to be the same as your headline) that are longer than 60 characters. Other than that, use active verbs, keep your language simple and try to address your reader directly.

7. Keep your copy consistent

Inconsistent copy looks sloppy. Although it might seem trivial, writing about ‘WiFi’ in one paragraph and ‘wi-fi’ in the next is an easy way to look like an amateur.

Whether you’ve had a never-ending list of spelling and stylisation rules imposed upon you by a pedantic client, or you’ve been afforded a little more creative freedom, you need to ensure that your language is clear and consistent throughout.

8. Proof read and then proof read again

If you’ve ever experienced the horror of discovering a typo in your published copy – even though you proof read it a dozen times – you’ll already know how difficult it is to spot these seemingly non-existent errors in something that you’ve written.

As explained in this Wired article: “The reason we don’t see our own typos is because what we see on the screen is competing with the version that exists in our heads.”

In an ideal world, your copy will be closely edited by a colleague who is an eagle-eyed wordsmith that doesn’t mock you for your incessant slip-ups. If this isn’t possible, Wired suggests doing whatever you can to “make your work as unfamiliar as possible.”

Whether it’s revisiting your copy at a later date, changing the background colour or printing your work out, these are all tricks that can help you catch errors yourself.

9. Cite your references

If you’ve written anything remotely academic before, you’ve probably had the importance of Harvard referencing drummed into you already. While the same rules might not exist online, it’s definitely a good idea to keep track of your sources if you’re carrying out your own research.

Whether you’re pitching to a journalist or you’ve just shipped your copy to a client, it’s highly likely that someone will ask you to verify a piece of information.

Rather than wading through your browser history to find where you sourced your facts from, you’ll save yourself a lot of time by keeping track of your references in the footnotes of a research document.

When it comes to publishing your copy, adding contextual attribution links or a reference list at the bottom of the page is seen as good etiquette and may even increase the chance of earning editorial links.

Now you’ve learned about some of the ingredients that go into writing killer copy, you’re hopefully itching to fill the blank Word document that’s been taunting you for so long. It might like feel there’s a lot of take in, but at the crux of copywriting is a common theme: flexibility.

The way you apply your skills is going to vary from project to project. One might see you trawling academic journals, while another might depend on your ability to get creative with a seemingly mundane topic. Think carefully about the context you’re writing for, do your homework and get good at editing ruthlessly. Only then will you be able to write copy that is truly engaging.

Richard Baxter

Excellent article, Alex. I think it’s worth heading to Natalie Nahai’s presentation on the psychology of copy next – this post + that presentation would make a killer combination!