What is a taxonomy?

A taxonomy in SEO parlance is a group of URLs with a common attribute which therefore share relevance with one another. A taxonomy of URLs does not need to follow a specific URL structure, nor does it have to sit within the same architectural depth from the homepage.

Taxonomies are purely relevance based, and while you might construct URLs of products say to sit within the same folder category, restricting a taxonomy to a single folder can result in missed opportunities to boost the relevance of the commercially valuable content.

In a recent architecture project, I discovered a gold mine of valuable commercial pages, but for some reason very few other users or robots were navigating to them. The URLs were missing key internal navigation links that users and search engine robots would use to find them.

I was asked to justify the existence of these URLs, or they would be deleted. Explaining the requirement of a coherent navigation without structure, specifics or evidence was not enough. To justify the upheaval of the client’s architecture, I started by grouping these pages by utilising taxonomies.

With the taxonomies created, it was possible to develop a hierarchy and grouping of revenue & traffic pages. Subsequently, this allowed us to make high impact recommendations, such as changes to the global navigation bar.

The implementation post-project led to an improved site navigation experience and increased authority flow to previously ignored commercial pages. Within six months of the project, we saw organic revenue for one of their taxonomy types increase by 128%.

Utilising taxonomies allowed us to map relationships between URLs without requiring them to be redirected. In the project mentioned, we included several evergreen blog articles within one commercial taxonomy to drive more relevance to those commercial landing pages.

Instead of changing the URLs, 301 redirecting and incurring fluctuation (which could also potentially confuse the user as they’d have to navigate through the blog), we kept the URLs structured on the blog, gave them a taxonomy grouping and applied internal linking rules between the commercial pages and the blog posts.

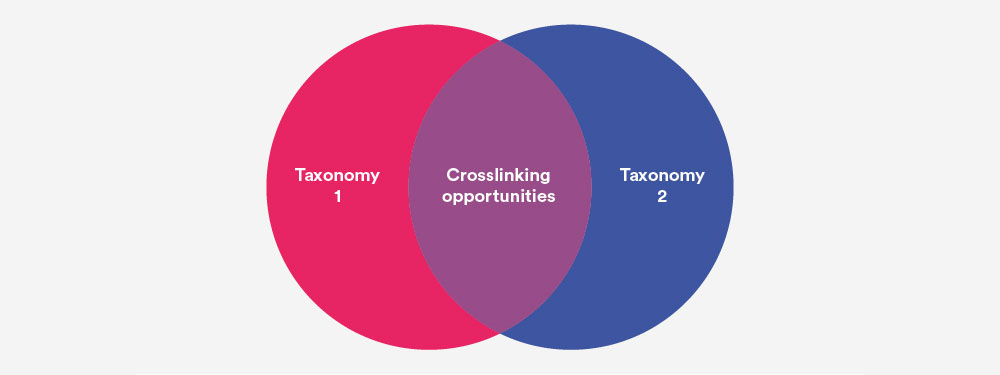

Using this framework, URLs can also be members of multiple taxonomies, whether that be:

- Hierarchal parent/child (marked by a primary taxonomy, secondary taxonomy, etc.)

- Or lateral (taxonomies with an overlapping commonality)

Using taxonomies in this way defines every one of your pages and may even uncover opportunities with pages previously assumed not to hold any SEO value.

Before we included blog content in the taxonomies for the insurance company, for example, the SEO value of the blog content was minimal. By including the evergreen content in the taxonomies, the blog could then be used to boost the relevance and user journeys between and to the commercial landing pages.

Taxonomies vs URL structure

Taxonomy (as a term in this framework) can be confused or conflated with the elements it can affect. For example, in meetings, it’s often used when referring to URL structure. While you can use taxonomies to build your URL structure, taxonomies don’t always need to follow the folder patter.

That said, using taxonomies can be a basis for your URL structure, particularly when you’re scoping a new site.

A record of URLs by taxonomy types, their hierarchy and lateral groups will help to answer questions like “what URLs should be included in the navigation bar?” and “what pages should we cross-link?”

What projects can taxonomies help inform?

You can use taxonomies in several project types and, once cemented, all future projects can refer to them. The three main areas we use taxonomies for are:

- Internal linking

- URL structure

- Site architecture

Internal linking

Two well-documented outputs of SEO work are improving the authority and relevancy of URLs. A common approach to achieve authority is to build external links, but internal links are also used by Google to establish authority and relevance. With a clear internal structure led by taxonomy, you can enhance relevance and authority to key commercial landing pages.

Having clear taxonomy groups laid out in a document helps you to answer:

- How are pages with different purposes relevant to one another? Viewing taxonomies holistically shows pages that not only naturally link but will be of interest to users and improve usability.

- How should products or services link to each other? Creating distinct taxonomies shows ways to cross-link strategies (for example, using “popular destination” in travel as a taxonomy).

You can read more about cross-linking in our comprehensive (and recently updated) site architecture guide.

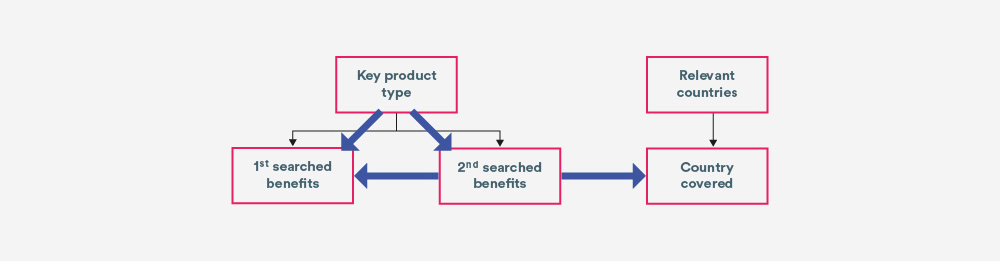

When we worked on the architecture for the insurance company, we divided the site’s commercial content into two taxonomies. Having this grouping in place meant we were able to devise several strategies that allowed us to link across categories:

As you can see, by implementing the recommended taxonomies, along with my own knowledge of the user, a link has been made between the key product and something it benefitted, which both sit within one taxonomy.

There’s also an opportunity to add links between two taxonomies – in the above case we added a link from the product to a relevant country. This results in the passing of relevance and authority laterally.

Why is cross-linking important?

If a site only contains hierarchal links, value is only passed within the pages’ hierarchy, and not across categories. Passing authority laterally through cross-links spreads the level of authority and relevance across taxonomies. By proxy, this increases overall authority for pages that may have high commercial value, but fewer hierarchal links.

URL structure

URL structure, in this instance, is the subfolders and categorisation of a website. As I said earlier, URL structure is often conflated with site taxonomy, and it’s easy to understand why. It’s normal to create the subfolders of a website based on taxonomies, as the primary taxonomies can often become the primary folder path.

Creating taxonomies can help you answer questions like “should this page sit off the root, or within another subfolder?”

For example, we recently worked on the structure for a client that was based in multiple locations with very similar products and distinct ways to purchase them. Their site had become cluttered with a number of new types of product pages that did not clearly distinguish themselves in the URL structure. The lack of URL structure sparked architectural issues for the website and saw content structured within multiple unnecessary subfolders.

Illustrated here is an anonymised set of pages that have replaced the product or service type with ‘something’.

| Name | Current URL |

|---|---|

| Do something | https://www.example.co.uk/example/do/something |

| Do something similar | https://www.example.co.uk/example/do/something-similar |

| Lessons for how to do something | https://www.example.co.uk/example/lessons/something |

| Advisory notice about something | https://www.example.co.uk/place/example/something-obstacle |

| Class for something | https://www.example.co.uk/example/example-folder-2/3rd-folder-level/something-classes |

| Membership for something | https://www.example.co.uk/memberships/example-folder/something-membership |

We divided the main areas of the site into clear multi-level taxonomies, allowing us to adjust the URL paths and give a clear structure for the user to navigate. For example, for the above list of related pages, the pages were assigned three taxonomy types, and we built the URLs based on that. Here’s how we did it:

| Name | Taxonomy 1 | Taxonomy 2 | Taxonomy 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do something | Products | Do | Something |

| Do something similar | Products | Do | Something similar |

| Lessons for how to do something | Products | Lessons | Something |

| Advisory notice about something | Products | Notices | Something |

| Class for something | Products | Classes | Something |

| Membership for something | Membership | – | Something |

Each of these primary taxonomies is then split into secondary taxonomies and within those we have tertiary taxonomies and so forth.

Depending on your CMS set up, some pages that share a key commonality but don’t sit in the same folder can result in a loss of relevance – particularly if they’ve not been linked to from the most relevant parent page, for instance categories to articles in a WordPress CMS. Furthermore, if a page isn’t properly categorised and structured correctly,

having the taxonomies mapped out helped us develop a URL structure and enforce a clear URL path, simplifying the URL for the crawling agent and giving the bot an indication of relevant pages.

Site architecture

Site architecture projects consider the actual hierarchy and linking structure of a site, with a focus on how users and crawling agents flow from page to page. Grouping your URLs into taxonomies by mapping keywords and search volumes presents you with different ways of encouraging users and robot user agents to crawl, click or tap through the website naturally.

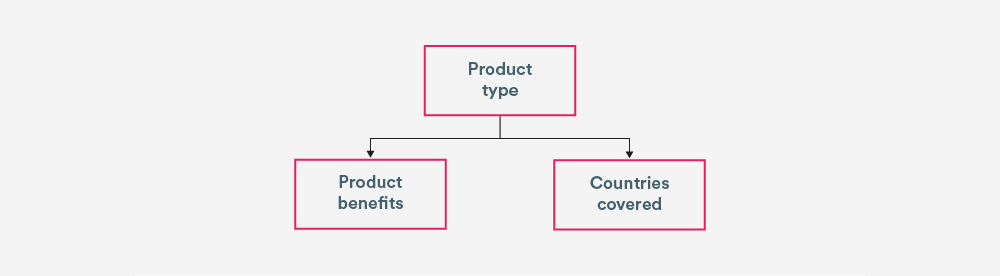

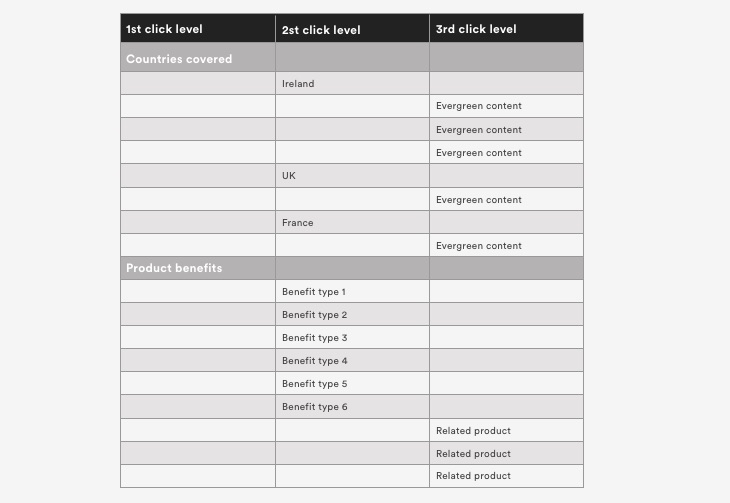

Here’s a simple example:

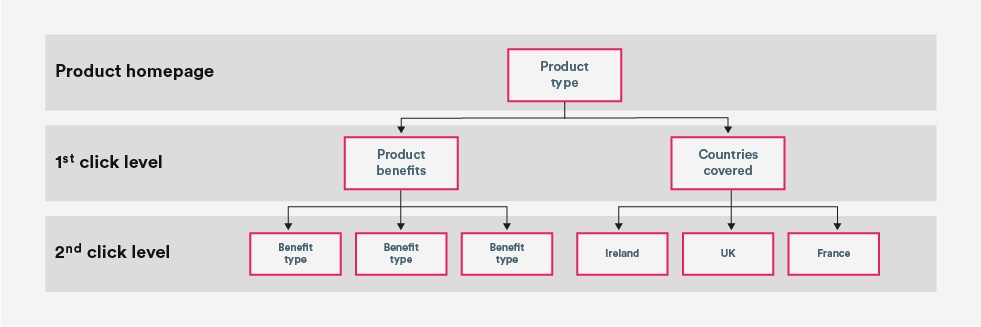

Once we had our taxonomies for the insurance client, it became much clearer how the site should look architecturally. In this case, the taxonomy work meant we could start building the architecture based on the primary taxonomies above and begin mapping out where each page would sit:

Site architecture based on taxonomies created

Viewing the taxonomies holistically also meant we could establish parent pages for each of the URLs. Parent pages are where the links that build your hierarchy sit and, more often than not, pass the highest level of authority onwards:

Please bear in mind that this approach suited the benefit types of the specific product offering of the client, how users were searching for it and the information that was present within those benefits. By delivering clear information on that particular benefit, the website reduced the time users required to understand the functionality of that product.

Users searched and were given at-a-glance benefits upfront, with unique information further down the page. Note that this is not always the most efficient or SEO-friendly way to deliver product information, depending on the vertical, but it worked for this client.

With the taxonomies and hierarchies agreed, we could implement changes to the navigation bar, including drop down menus for each of the taxonomies based on the commercial values of each of the URLs.

Finally, once the architectural hierarchies were established, we could look at including cross-links between taxonomies and website categories. This included looking at adding sections like “Related pages” or “Find out more” that included links to pages elsewhere in the site.

And there you have it.

With a bit of investigatory work, spring cleaning and forward planning, you can drive your SEO strategy, boost the value of your links and create a better user experience with taxonomy.

Glossary

- Taxonomy: a group of URLs with a common key attribute which therefore share relevance with one another, regardless of URL path.

- Hierarchal taxonomies: parent/child relationship of taxonomies, therefore assigning URLs with multiple taxonomies – primary, secondary, tertiary etc.

- Lateral taxonomies: a taxonomy sitting in the same hierarchical level (e.g. primary taxonomies) across a set of pages.

- URL structure: the physical makeup of the URL, which identifies the URL folder structure.

- Site architecture: the depth and relationships in the linking structure of the site, regardless of URL path.

- Internal linking: a link between two URLs on the same website, therefore passing authority and relevance.

- Cross-linking: linking between taxonomies and architecture hierarchies to spread authority laterally across the site.